Winson Green Asylum. Birmingham UK

The Victorian Era may not have been the start of the institutionalisation of patients with mental health problems, but it was certainly a period when the numbers of asylums and patients treated within them, exploded.

The first known asylum in the UK was at Bethlem Royal Hospital in London. It had been a hospital since 1247 but began to admit patients with mental health conditions around 1407. Not that the term mental health had been coined at that time. Patients were often considered as ‘mad’ as suggested by The Mad House Act of 1774. This was superseded in 1853 by The Lunatic Asylums Act. As the name of the legislation suggests, there was little concern for patient’s sensibilities, and typically patients were described as lunatics, imbeciles, insane, idiots or cretins.

The growth in the number of asylums was largely driven by the County Asylum / Lunacy Act. This act meant that Counties were legally obliged to provide asylum for people with mental deficiencies. Between the passing of the act in 1845 and 1890, when the next act was passed, over sixty asylums were built and opened. A further forty were subsequently built. Eventually, asylum numbers reached a peak in the 1950s with over one hundred hospitals and approximately 150,000 patients in England and Wales.

Admission to the Asylums – What should have happened

As with many areas of society at the time, the admission into asylums was based on class. The upper and middle classes could admit family members who were suffering from some sort of mental trauma as private patients. Those with little or no funds, however, were admitted as paupers.

To avoid abuse of the system, the 1853 Lunatic Asylums Act, laid down guidelines for admitting patients to the asylums. In order for the detention of pauper lunatics to be legal, they required the appropriate paperwork on admission. This included a medical certificate signed by a doctor or apothecary (similar to a modern day pharmacist), who had personally examined the patient within the previous seven days. In addition, an order from a Justice, a Clergyman, an Overseer, or the Relieving Officer (under the Poor Law) was required.

Private patients needed a medical certificate signed by two physicians, surgeons, or apothecaries.

In both cases, detailed information about the patient was also required. This included: name of patient; sex and age; married, single or widowed; condition of life and previous occupation; religious persuasion; whether this was their first attack; age at the time of the first attack; duration of existing attack; supposed cause; whether the patient was subject to epilepsy; whether they were suicidal or dangerous to others.

Once admitted, there was no procedure for the patient to appeal against detention. They could, however, be discharged on the application of a relative or friend, as long as they confirmed that they would take proper care of the patient and prevent them from injuring themselves or others.

Admission to the Asylums – What did happen

Despite the good intentions of the 1853 Act, it appears there was still plenty of scope to abuse the system. Unfortunately, for many, asylums were regarded as prisons disguised as hospitals. It was a convenient way to remove the poor and incurable from society and for those with money, private madhouses were often convenient dumping grounds for unwanted wives.

Despite the good intentions of the 1853 Act, it appears there was still plenty of scope to abuse the system. Unfortunately, for many, asylums were regarded as prisons disguised as hospitals. It was a convenient way to remove the poor and incurable from society and for those with money, private madhouses were often convenient dumping grounds for unwanted wives.

Although many patients were admitted for short periods of time, there are plenty of stories of patients who were admitted to asylums, often for very unsatisfactory reasons, and basically forgotten about. Some could spend twenty or more years locked away, and sadly some patients died without ever being released.

The chances of admission were higher if you were a woman

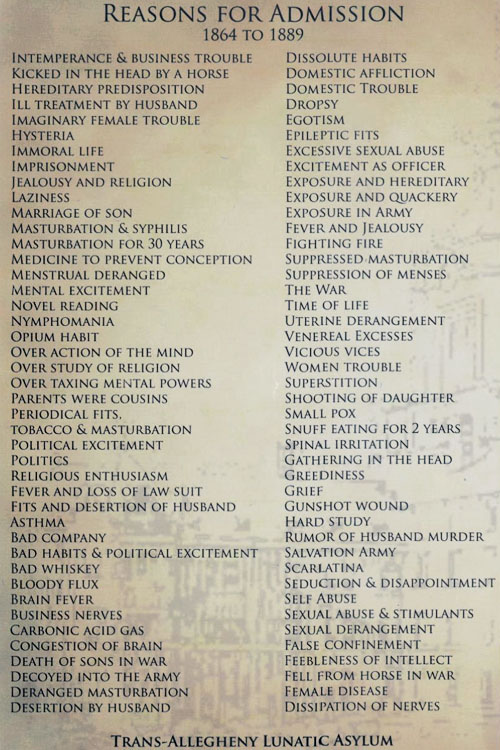

Reasons for admission were very much down to personal judgment and seem to have been heavily weighted against women. Indeed there were often many more women compared with men confined in these institutions. The attached poster from the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in the US describes many reasons patients were admitted. Anecdotal reports suggest that similar practices occurred in the UK.

Depression associated with various situations seems to be common. Examples listed include valid reasons such as ‘death of sons in war’, ‘desertion or death of husbands’ and ‘domestic trouble’. Many other reasons, however, are much more spurious. For example, ‘imaginary female trouble’, ‘immoral life’ (often associated with carrying &/or delivering an illegitimate child), ‘menstrual problems’, ‘the menopause’, ‘uterine problems’, ‘female disease’ and ‘nymphomania’.

‘Hysteria’ is also cited as a reason for admission. This is, however, a subjective assessment and one that was easily abused. Women at the time were expected to be demure, polite and agreeable to the men in their lives. Should a women dare to speak out of turn or argue with her father or husband, however, she could be considered hysterical and in need of treatment.

Equally worrying was that women were admitted if they had ‘over action of the mind’. This could be because they wanted to educate themselves, or for some, it may have been as simple as wanting to read. Indeed, ‘book reading’ is listed as a reason for admission to the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum.

Life inside the Asylum

There were strict segregation rules within the asylum. On admission, patients were known to be either private or pauper patients and were housed in wards appropriate to their status. Whereas private patients had fewer beds to the ward and some degree of privacy, pauper wards contained as many beds as the hospital could accommodate, meaning there was barely space between the beds and no privacy.

In addition, there was strict segregation of males and females, with wards being housed in different wings, or even separate buildings, within the hospital.

Life inside the asylum was one of routine and orderliness. Patients were woken at 7am and given a breakfast of tea, coffee or cocoa with porridge and bread. A midday meal, (the main meal of the day) was served at around 12.30pm. A tea of bread and cake would be served around early evening, just before the patients were sent to bed for the night.

Outside of meal times, routines differed for men and women. One of the most common jobs for the men was to work on the farm. Many asylums tried to be self-sufficient and much of the food consumed by the patients and staff was produced on the farm. Many men also worked in the bakery, to produce their own goods, or in the kitchen.

Women, however, were usually kept indoors. The laundry employed the majority of them, while many more were kept busy mending in the needle room. A proportion of both sexes would be expected to do cleaning duties around the wards.

For those patients who wouldn’t or couldn’t work, the airing courts would be opened for an hour in the morning and afternoon so that they could take the air.

In the early days of the asylums, security was tight and patients were only let out of doors under heavy security. As time went on, however, the rules were relaxed and patients were encouraged to go outside and even interact with other people.

This was especially true for men, who were they allowed to tend the garden or join sports teams. These activities were not permitted for women, however, and other than a gentle walk around the gardens they could expect to spend their time indoors.

Treatments:

For the greater part of the Victorian Era, treatments for most conditions (psychiatric or otherwise) primarily consisted of physical treatments such as surgery. With a few notable exceptions (Laudanum; Strychnine), drug treatments were not available. The treatment of the mentally ill was no different.

There was little understanding of the causes of mental illness and one of the main aims of treatment was to keep the patients calm and relaxed. This may have been achieved by the routine set by the hospital or the strict supervision, but for those patients who couldn’t or wouldn’t be settled, there were several additional options:

Restraints and the padded cell

Physically restraining patients with straight jackets or fastening them to beds was one of the easiest ways of controlling those with excitable or aggressive behaviour. It was also used for patients thought to be at risk of suicide. As an alternative, patients were placed in isolated padded cells for short periods of time. These rooms contained nothing, and the walls and floors were covered with leather or canvas pouches filled with horse hair, to prevent patients from harming themselves.

Water Therapy

Water was a popular way to treat a variety of conditions. Cold water, either in the form of a bath or shower, was used to calm down aggressive or excitable patients, while warm water, usually in a bath, was used for patients with melancholy. Warm water therapy could be soothing. Patients would be put into a bath, sometimes on a canvas hammock held in place by a metal frame, and covered with warm or body temperature water up to their chin. The bath was then covered with a canvas sheet, with a hole for the patient’s head, and they would be left there for hours, or sometimes days. The colder water was allowed to drain from the bottom of the bath, while warmer water was constantly added.

Cold water therapy, on the other hand, could be extreme. In short, sharp bursts, of about fifteen to twenty minutes, it was used to reduce those in a highly excitable or manic state to calm, obedient patients. Treatments varied by institution and doctor, but techniques included:

Cold water therapy, on the other hand, could be extreme. In short, sharp bursts, of about fifteen to twenty minutes, it was used to reduce those in a highly excitable or manic state to calm, obedient patients. Treatments varied by institution and doctor, but techniques included:

- Tying the naked patient to a chair and pouring buckets of cold water over their heads.

- Restraining patients in cold shower rooms, or shower-baths, and spraying water into their faces as well as onto their bodies.

- Using chairs to immerse patients into small ponds until they were at the point of unconsciousness before they were removed from the water and allowed to recover. This process could be repeated until the desired outcome was achieved.

In patients who failed to respond to the initial therapy, or if the physician thought they might ‘re-offend’, treatment was repeated. Sometimes it could go on for hours, while for others it was repeated daily until the patient was felt to be in a satisfactory state of mind.

Some physicians were so fond of water therapy, they saw it as a means of corrective therapy, to ‘encourage’ the patient to adopt the behaviour expected of them.

Drug Treatment: Paraldehyde

While there were very few drug treatments in the Victorian Era, paraldehyde (a sedative that calms the nervous system) was introduced into UK clinical practice in 1882. It was found to be useful to treat convulsions (fits), as well as induce sleep. Indeed, it was so effective at inducing sleep; patients would often be given paraldehyde after their early evening tea to quieten them down for the night and to make it easier for the nurses to get everyone to bed.

It wasn’t until the twentieth century that newer treatments were introduced although some, such as ECT (Electroconvulsive therapy) and lobotomy (removal of parts of the brain), were not necessarily an improvement. Modern-day anti-depressants and antipsychotics only started to make their way onto the wards around the 1950s.

Conclusion

By the 1960s, the asylum system in the UK had become too big to manage, and although effective treatments were still in their infancy, it was announced in 1961 that many of the hospitals would close. It was another twenty years, however, before the closures began. Now only a handful of the old institutions are still in existence and most patients receive their care in the community. Whether this is suitable for everyone is still a matter for debate, but it is safe to assume that the existence of asylums, as they once were, are unlikely to ever form an integral part of mental health treatment in the future.

This information was gathered as part of the research for the Ambition & Destiny series. Click here to find out more.

References:

- The Time Chamber

- A Stroll Down Memory Lane: The Lunatic Asylums Act 1853

- Madness in their Method: Water Therapy in Georgian and Regency Times

- A brief history of healthcare provision in London

Back to The Victorian Era